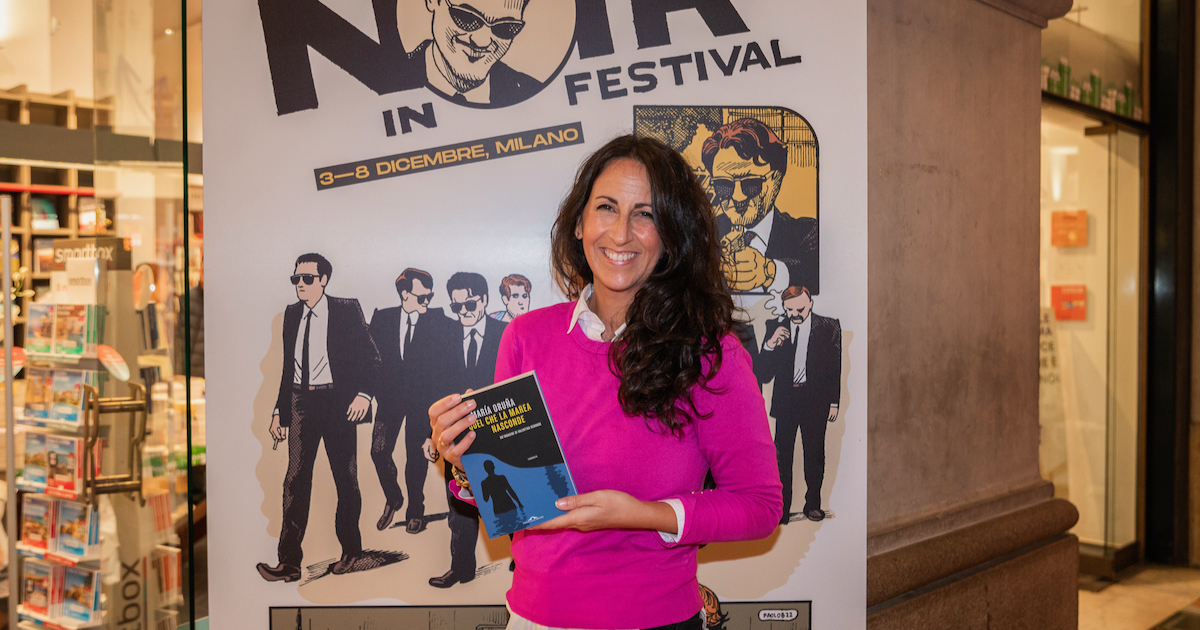

Two female authors present their latest novels at the Rizzoli Bookshop: Cinzia Bomoll, with La ragazza che non c’era, and Marìa Oruña, with Lo que la marea esconde.

An article by Ariel Conta

Women have always been central to noir fiction, whether caught in that second that divides light and shadow, or so beautiful that there is no way back. And this wealth of shades of light, darkness, and meaning doesn’t discourage contemporary women writers in the noir vein, who bequeath this treasure, like an heirloom, on their female protagonists.

A prime example is La ragazza che non c’era (Ponte alle Grazie), the first noir novel by Cinzia Bomoll, who presented it on Monday at the Rizzoli Bookshop. It’s a story in chiaroscuro, like the region Emilia in which it is set. When asked about that setting by moderator Isabella Fava, Bomoll declared: “I started to write the novel during lockdown, and that’s why I chose to set the story in Emilia: I’d returned to the region after several years of living in Rome. It was a form of nostalgia.” Indeed, she had this to say about the main character of the novel, a woman: “I tried to instill the geography and environment in the character of Nives.”

Screenwriter, author, and filmmaker: Bomoll’s identity swings between words and images. After the recent release of her new film, La California, Bomoll once again explores female characters immersed in a countryside of somber hues, this time not on the screen but on paper. She describes her own “passion for storytelling in written form”, but she leans to “writing through images”; in sum, it’s a “passion with two different facets: two ways of seeing and feeling things,” Bomoll explains.

During the talk, in a further blurring of the line between cinema and literature, actress Eleonora Giovanardi – who plays Palmira in La California – read two passages from the novel. “Who ever said that hell is below us?” Nives wonders, as Giovanardi lends her own voice to the character. The question underlines, once again, this human geography that is conflicted yet representative of an individualism that can’t be tamed.

These personality traits are also found in Lo que la marea esconde (Ponte alle Grazie) by Marìa Oruña, published in Italy for the first time. It is the fourth installment of a series revolving around Valentina Redonda, lieutenant in the Guardia Civil.

As the author declared in her dialogue with Fava, Valentina “is characterized by a remarkable dualism; she’s a contradictory figure. I wasn’t looking to create a super-intelligent investigator like Poirot or Sherlock Holmes, who know all and handle every aspect of a case: that would be a bit anachronistic today […] they’re static characters. The moment when this novel takes place is fundamental: Valentina is a broken woman, broken inside. Will she be able to resurface and survive, or let herself be dragged into the depths?”

Once again, the setting reflects the character’s inner state; the crime that is the springboard for the story takes place on a schooner: a space suspended between water and land and nature and culture. Guiding readers through these splashes of darkness are quotations from classic mystery novels. “The book is composed of different layers that the reader discovers a bit at a time. Every quotation,” the author continues, “was meant to be a provocation, an alert I provide the reader, a clue to arrive at the truth.”

As Fava mentions, before she became a bestselling author, Oruña was a lawyer, and it shows in her literary style, taking the form of areas deliberately left in shadow and not illuminated for some time. “We lawyers are known for weighing our words, […] and paying maximum attention to shades of meaning,” she explains, “and this aspect of my former profession certainly came in handy when I turned to novel writing.”

Women in flesh and blood and women on paper coexist in contemporary noir fiction, which is heightened by a wide range of tones and hues even as it plumbs the darkest twists and turns of the genre.