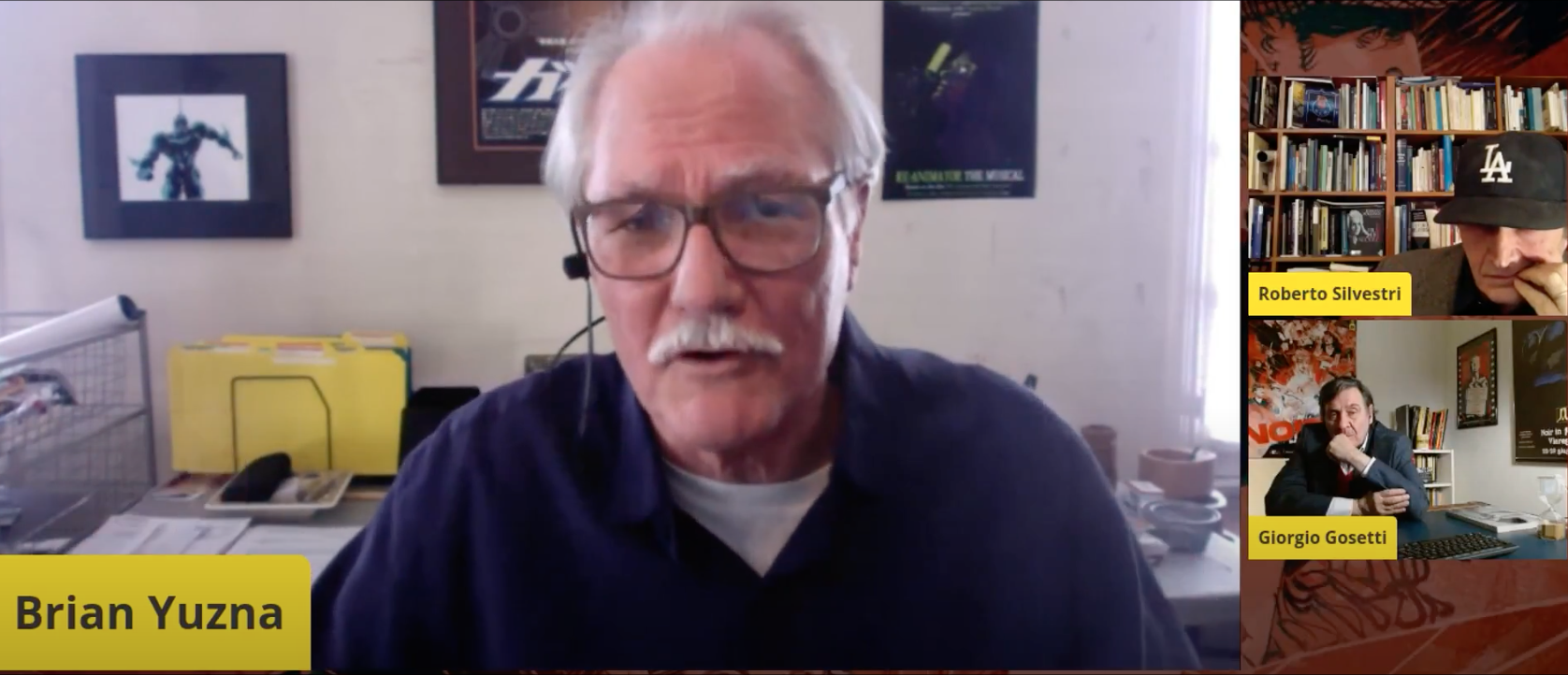

Brian Yuzna, winner of the 2020 Luca Svizzeretto Prize, picked up the gauntlet thrown down by Roberto Silvestri and Giorgio Gosetti and held nothing back, musing over his love of genre films, his start as a self-taught director, his commercial work, the 1980s, special effects, and more.

“I’ve been mostly outside the mainstream of filmmaking, which meant that most of my productions are small”. With this introduction, the winner of the 2020 Luca Svizzeretto Prize, Brian Yuzna, launched his conversation with Giorgio Gosetti and Roberto Silvestri, and then explained: “It wasn’t on purpose. I would have loved to make huge movies but it seemed to be how things worked out for me. There is an interesting aspect to me as a filmmaker, which is that I didn’t begin to make movies until I was already in my thirties. So I already had a wife and kids. So that meant I never took any movie classes or studied film. And I learned how to make movies just by trying it. For the first one, I just looked at books – that’s Self Portrait in Brains. But for the other ones, I just came to Hollywood and I learned by watching the people that I hired.”

After Silvestri introduced Yuzna in terms the latter mostly approved of, making a few small, good-humored corrections, he asked the independent filmmaker par excellence just what he thought of the directors making horror movies today. Yuzna highlighted one particular difference, that between special effects and digital effects, which he felt was the game changer from the 1980s generation of directors to those who came more recently.

“I know effects artists who can put their hand in a sock and make it come to life. It’s a performance. The digital is animation. It’s very, very sophisticated animation, but it’s animation. And it requires many, many, many people to create that animation. So it’s very difficult to do well without a lot of money, more money than independent movies can have, really. And it’s very hard to be able to perform with those effects. I only had one experience with doing digital effects. The movie I made in Indonesia was called Amphibious. It was the story of a giant sea scorpion, and I built the whole sea scorpion in the jungle in Bali, with people who had never been on a movie set and wouldn’t even sit in a chair – they worked on the floor. But we built the giant sea scorpion that took eleven people to move with hydraulics.

“And I tried to make a puppet sea scorpion, a small one, because I knew that, with a puppet, you could just keep shooting until you get something that works, whereas with digital, once you agree on the animatronic, then the next guy comes in and puts on the skin, the next guy puts the lights, all digitally, but you can’t just work it. There’s many layers, not just one person who is animating it. And unless you have a tremendous amount of money, unless you’re doing Jurassic Park, you don’t see – you can’t just tell’em, ‘No. Change that’, because they have to throw it out, go all the way back. So there is a difference between puppetry and animation. I think digital effects are really good,” Yuzna added, “for erasing strings or rods to manipulate the puppet. And I think it’s good to augment. So, for example, the real sea scorpion that I made has got a big face but the eyes don’t seem alive. There’s things that you can’t move really fast with puppets. There’s limits to it. So what I used the digital for was to augment it. I made the eyes and the mouth move digitally.”

Prompted by Gosetti, Yuzna told the rather unconventional story of how he fell in love with horror. “Like most people, I tried to make movies like the ones I loved when I was a kid. So I think this is pretty typical: you make movies based on movies that you’ve seen. I always like horror and in art I always like surrealism and expressionism. Both are kind of dream-like art forms. For some reason, I saw some horror movies when I was very young, and they really infected me. I learned to love these movies, and I was very influenced by that. I like all cinema. In the 60s, the best cinema was the art cinema, of Fellini, you know, Bergman…And I loved those movies, but I wouldn’t have dared to make one. So this is where the commercial side comes in. When I began making movies, I began by producing. I raised the money, I borrowed money: I didn’t have the luxury of failing. I had to get the money back. And I noticed with horror movies – I’m a fan – that there will always be some audience for that.”

So in the end, just what is Yuzna’s ideal horror movie?

“Well,” he replied, “I think my idea of a horror movie is Re-animator by Stuart Gordon. I don’t know how you get something that is any more of a horror movie. Looking at that era, two other important movies came out: Evil Dead and Return of the Living Dead. They’re fun, they’re horrific, they’re gory; there’s sex, there’s death. Each one is different but they’re all very similar. I like horror that has a sense of irony to it. One of the great things about making genre movies is that once you put the elements of horror that the audience expects in the movie, you can do almost anything else you want. I always think that if a movie is scary, you could call it a thriller. If that thriller, now, has some kind of fluid – blood, goop – then it’s a horror movie. And then if you add something metallic, then it starts being science fiction.”