The dark side of Francoism

Barcelona’s police procedurals

Barcelona’s police procedurals

by Esteve Riambau

Director of the Filmoteca de Catalunya

While the discussions over the fascist uprising that brought Franco to power were one of the major trends of Spanish cinema in the 1940s, religious cinema was imposed only in the following decade.

Censorship was severe and, besides the official censors, extended to other organs of power in the repressive state: the Church and law enforcement. Curiously, it was around the latter that Spanish cinema developed a genre, the police procedural, which introduced moderately critical social elements and adapted international film and literary models. More so than French noir, North American noir cinema and B-movies in particular served as models for approximately 65 films that, from 1950 to 1963, reflected Spain’s social problems at the time - crime, prostitution and extreme poverty - without roiling a police force that was absolutely irreproachable under the authoritarian regime.

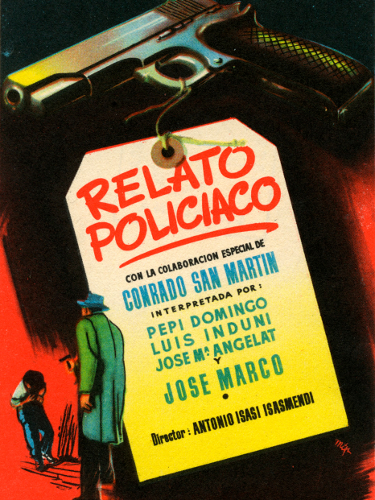

The fact that many of the films were produced in Barcelona-based companies proves that they were low-budget films that replaced studio productions with scenarios of everyday life, thus becoming realistic portraits of urban life in the Catalan capital, which was actually the protagonist of some of these films. The publicity campaign for Relato policìaco (Antonio Isasi Isasmendi, 1954) unabashedly billed it as the "first truly realistic Spanish film."

The voiceover heard at the beginning of Apartado de correos 1001 (Julio Salvador, 1950) sums up all these considerations in the typical language of the era: "Always at the avant-garde of national cinema, Emisora Films wanted to a make a film different from the others. A film that for the first time on our screens incorporates the realistic emotions of the most pressing current events. The story is based on one of the many instances that regrettably take place in any big city. It is the quiet and altruistic story of a group of dedicated, honest men who risk their lives for the sole purpose of defending society from all those who seek to destroy it. This film was shot in the same streets, squares, buildings and exteriors in which it is supposed the real events could have taken place."

At the margins of the innovative nature of this genre of Spanish cinema, of the demand for a realism that censors systematically denied all films at the time - domin ated by confrontations between young and veteran police inspectors or the creation of our own prototype of the femme fatale - that which the prologue of Apartado de correos 1001 did not explicitly state was its fierce competition with Brigada criminal (Ignacio F. Iquino, 1950). Francisco Ariza and Ignacio F. Inquino, the films’ respective producers (and brothers-in-law, no less), poured their personal conflict in these films, which drove the latter to break away from the former’s company to work on his own projects. It’s hard to say who copied whom, but it’s obvious that the stylistic and narrative similarities of the two films were not random, and from that moment became a recurring trend that was developed through to the early 1960s.

Besides these two groundbreaking titles, this retrospective includes two films directed by Josep María Forn - Yo maté (1955) and ¿Pena de muerte? (1962) - and two by Francisco Rovira-Beleta: Hay un camino a la derecha (1953) and Los atracadores (1962). Antonio Isasi Isasmendi, screenwriter and editor of Apartado de correos 1001, made his directorial debut with Relato policíaco, starring Conrado San Martìn, the young seducer of the previous film. The film was produced by Balcàzar, the Barcelona-based company that, before moving into European co-productions of westerns and spy movies, made the first foray into the police procedurals by first-time filmmakers: e.g., Forn’s Yo maté and Paco Pérez Dolz’s A tiro limpio (1963).

IFI, in turn, besides producing Brigada criminal, also made Mercado prohibido (Xavier Setò, 1952). Further coincidences can be found: Josè Suarez, the star of this film, was also in Brigada criminal while seducer Juliàn Mateos appeared in No dispares contra mi (Josè Marìa Nunes, 1961) and Los atracadores.

Most of these were B-movies, whose low budgets kept them far from box office success. They evolved from adapted theatre plays, radio dramas, comedies and diverse collections of popular novellas. Spanish critics and cinephiles very much liked the references to North American cinema in the form of homage, such as in Apartado de correos 1001, which pays tribute to the protagonist of the urban scenario in The House on 92nd Street (Henry Hathaway, 1945) and the ending in the amusement park that harkens to The Lady from Shanghai (Orson Welles, 1948); or the appearance of Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1959) in the background of No dispares contra mi. But despite these "games of influences," these films took on their own personalities, which were criticized by Madrid at the time. Using Los atracadores as an example, the left-wing magazine Nuestro Cine wrote disdainfully about "these films small-time gangsters; reticent, young good-for-nothings; formal ostentations of the worst kind; seedy smugglers; ultra-chaste sexual morbidity."

More than 50 years later, however, those Barcelona produced crime dramas continue to garner attention as an atypical blend of Hollywood noir influences and praise from the local police that carried out the repression of Francoism; as a realistic portrait of Barcelona’s urban environment - with exceptions in Madrid (Brigada Criminal) and extensions to all of Catalonia (Relato Policiaco); and an aesthetics of the era that was dominated by plasterboard sets, by some Madrid filmmakers whose artistry matched the pomposity of their films and other artisans, in Barcelona, who used their talents to tell cops-and-robbers stories. There were important pioneers of Catalan cinema, such as Segundo de Chomòn; activist filmmakers like those who made Republican propaganda newsreels during the civil war; and avant-garde movements like the Barcelona School.

But there were also genre films, in this case noir movies, that sought their niche between imitation and invention in order to grab audiences that, at the very least, could appreciate their attempts to skirt the asphyxia caused by Francoist censorship.